The Sound of The Woman That Loves You

On the endurance of love, art, and Fleetwood Mac.

In 1977, the same year as the Voyager 1 Golden Record was launched into space, Rumours was released. No songs from the album feature on that record. Here on earth, its cultural impact and endurance almost fifty years later would be astounding, if it weren’t for the fact that it is one of the best records ever made. Its original tracklist did not include Silver Springs.

The love story of Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham is so public that it feels like it belongs to everyone. The details of their relationship brought into such sharp focus through their records, performances, and interviews make these people and their romance feel so real to us that they appear more like public domain fiction than fact. The moments of their lives crystallised in the music have allowed it to transcend celebrity gossip status into the canon of great love stories. It feels so real to the public, such a perfect tragedy, that they are often treated like characters in a story than actual people.

Despite how easy it is to mentally write fanfiction about star crossed rockstars in your head while you listen to Fleetwood Mac, or how fun it is to put videos of them performing on the TV1 and scream at with your friends about how much they love each other (guilty!), the pair are very much real people with their own private lives. However, I am not here to speculate on the nature of those, but rather on why the music and its mythology possess such endurance in our cultural consciousness.

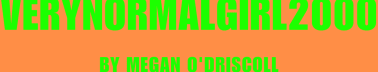

Watching a live performance of Silver Springs is like walking in on something you weren’t supposed to see. If it feels like a very private moment between two people with a long and complicated history, it’s because it is. It’s also not that at all, because it’s a YouTube video of a concert with an audience of thousands watching one of the most famous bands of all time.2

When they play Silver Springs, however, you are not just watching two people perform a song about something that happened in the past. You are also watching the story of the song playing out in real time as a man fails to escape the sound of the woman who loves him. Stevie Nicks locks eyes with Lindsey Buckingham, who looks like an animal caught in a trap. Singing backup vocals, he helplessly repeats that he’ll never get away from the sound of the woman who loves him. Decade after decade they have performed this song, and the curse that Stevie Nicks wrote in her lyrics becomes real over and over again:

Time cast a spell on you

But you won’t forget me

I know I could have loved you

But you would not let me

I’ll follow you down

‘Til the sound of my voice will haunt you

You’ll never get away from the sound

Of the woman that loves you.

Many songs on Rumours, specifically many of the songs about Stevie and Lindsey’s relationship, are composed of absolutes. If you don’t love me now, you will never love me again. Loving you isn’t the right thing to do. When the rain washes you clean, you’ll know. The songwriters speak as people who have long since made up their minds, as people who can’t quite make up their minds often do.

Silver Springs does involve some begging (give me just a chance) but it is a song situated firmly in the aftermath of something incomprehensibly massive that cannot be undone. It’s about a time before, that you can only visit in your own memory and feel in your own heart, knowing you can never truly go there together again. As the poet Maggie Smith says in After the Divorce, I Think of Something My Daughter Said about Mars, if you go / You have to stay gone. Staying gone has never been the strong suit of Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham.

Silver Springs is a song of woulds and coulds that predicts the future because it cannot change the past. Sometimes the most life changing love, or the love stories that capture our imaginations the most, are about love that could not - by nature or by circumstance - work. Maybe the reality of the relationship described in Silver Springs is that it was right for Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks not to end up together, but that tension between what we want and what we can’t (or shouldn’t) have is where this song lives. Even when the dust has settled, we can’t resist the drama of dredging it all up again, taking it out to look at even though we know that it will rust when exposed to the air. It’s the musical equivalent of picking at a scab.

Often, we are willing to accept the implicit assumption that beautiful art must have been made about something that is itself beautiful. If it weren’t for songs like Silver Springs, or their broader context within albums like Rumours or Fleetwood Mac’s discography, would we really care about the story? I am sure that every day on this earth there is someone somewhere possessed by frighteningly, maddeningly intense, true love. They just couldn’t write a song about it.

Some of the greatest love songs of all time have been written about deeply dysfunctional and what would appear up close to be somewhat uninspiring relationships. The artist takes the experience and the feeling and transforms it into something greater than the sum of its parts. Although, in their eyes, the experience and the art may be equally profound.

This process of artistic transformation remains mysterious, and begs the question: would the story of Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham matter to us if they weren’t able to create such incredible music about it? Maybe not. If I have to hear about a stranger’s shitty boyfriend, I’m hoping they at least know how to tell a good story. Whatever Stevie Nicks was going through when she wrote Silver Springs might have been profoundly uninteresting to the world were she unable to write this song about it. It’s because she was that she and Lindsey Buckingham continued their ascent to almost folk hero status, not as songwriters, but as lovers, even as their actual relationship continued to deteriorate.

Stevie Nicks has written some of the greatest songs of all time. She allegedly wrote Dreams in about fifteen minutes in some corner of Sound City. The studio recording of Dreams uses the guide vocal that she recorded just to have something to base the instrumental tracks off of because it was already the perfect take. She also called the deeply mediocre Harry Styles album Fine Line “his rumours” and claimed that the campy Twilight sequel New Moon “changed [her] life.”

I’m glad that Stevie Nicks has found meaning and joy in these things, but I think these instances clarify that her artistic ability and taste are not one and the same. A person doesn’t need to be an arbiter of taste to have the spirit move through them to create something beautiful. Much like how those with great ability to consciously examine and dissect what makes “good art” often struggle to produce it themselves, the artist can be a vessel for something beautiful emanating from the subconscious without always having influences (artistic or experiential) of the same calibre.

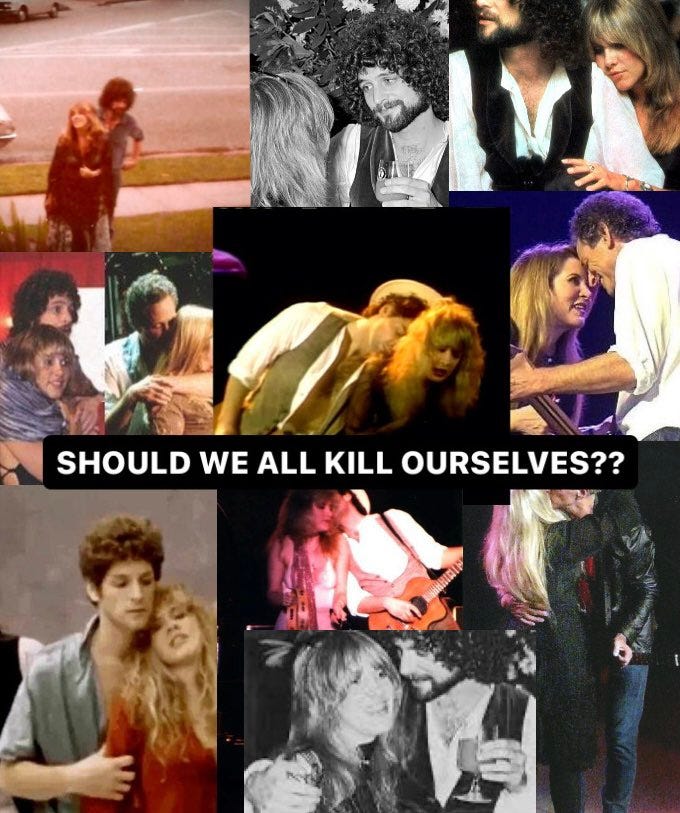

As much as it is incredible to be able to transform moments and feelings known only to you into works of art that the rest of the world can understand, it’s also kind of awful. Lindsey Buckingham had to contend with the inescapable sound of the woman who loves him for years, but what is often overlooked is that so did Stevie Nicks. Live performances of the song are often construed online as her torturing him, hexing him, but these readings also overlook the ways in which she herself is trapped.

Despite how her feelings may have continued to grow and change (the song itself includes the line I begin not to love you), Stevie Nicks always has to reproduce the sound of the woman who loves him, present tense, night after night. Every time I watch a video of her performing Silver Springs, the sound of the woman who loves him comes out of her body, regardless of whether or not she is still that woman. In some recordings, there seems to be a mutual respect and affection between the pair, in others there is only hurt and resentment, but the sound is always that of the woman who loves him. For the runtime of the song, she exists once again, regardless of whether either of them want her there.

The scope of the personal implications of this for the pair are difficult to comprehend. How do you tell someone over and over again that you could have loved them and they’ll never get away from you without that having a severe impact on the both of you? How do you perform a song like that with Lindsey Buckingham’s wife looking on? How do you talk to each other before or after that show? How do you look each other in the eye off stage, or look at the other people in the band when everyone just saw your public confessions and condemnations?

Maybe my inability to answer these questions is, among other things, the reason that I am not in Fleetwood Mac. While that’s probably for the best, it doesn’t stop me from asking. When we go beyond the music, it’s these questions that are the basis of the enduring fascination with the song and the band.

As much as witnessing a performance of the song gives the impression that Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham are the only two people in the world, or at least the only two that matter, there are always other people involved in love and in art. In some ways I do pity the rest of the band for having to watch them get up and perform those songs night after night for so long, saying everything they crystallised in the music back in the late seventies, while also not being able to say much of anything at all up on stage together.

As Lindsey Buckingham said in a 1987 interview, "Everyone is a little crazy underneath the surface, I just think we're a bit more exposed than most.” 3 To watch two people you know and care about endure those emotions so publicly and so repeatedly while you continue to play in the background seems horrible, aside from the obvious comforts of literally being in Fleetwood Mac.

The tumultuous relationships between Fleetwood Mac members affected every member of the band. No matter who you cast as victim or villain or tortured artist or just coked up young megastar in any particular version of events, they were all there, influencing and in turn being influenced by the ups and downs of the band’s often publicised personal affairs. In doing so, every member of the band became part of the story and part of the sound. The presence of the rest of the band in Silver Springs is as noticeable in their absence on songs like Landslide.

Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham may have been the only two people who knew what it felt like to be in their relationship, but all five of them together were the only people in the world who knew what it felt like to be in Fleetwood Mac. When the sound of the woman who loves you is so enmeshed with the sound of the only other people who experienced something so life altering with you, is it any wonder that you’d never get away from it? Maybe you would never want to.

Maybe the only way you can get to that place again, where your friends are alive and young and about to be skyrocketed to fame that would change everything is to sublimate yourself to the song. To be back on that planet, back breathing that air, maybe you have to let the version of her that wrote the song speak to the version of you it was about and vice versa. You can almost go back to that place if you slip back into old skin and embody those people and, for just a few minutes, let time cast the spell on you.

Sometimes I worry that in my own work I perform a similar type of flagellation, not to the degree nor with the cultural impact or even talent of Fleetwood Mac, but with a similar emotional toll for myself and others. A lot of the poetry I write and publish is about other people, it’s almost all I know how to write about. Some of those people are no longer in my life, and among those, some make a point of reading what I had to say about them. I can’t say I would do any differently in their position.

I worry that this is inappropriate of me, that public negotiations of emotion so one-sided are inherently unfair. I comfort myself with the fact that pretty much no one reads that shit, so it’s probably fine, but I know that it’s the principle of the thing that really bothers me. Sometimes I think maybe making art about human relationships is the only appropriate thing to do and that sharing the art we make with other people is a necessity. If it’s good enough for Stevie Nicks, who am I to disagree?

Just as Silver Springs is a song about how we can’t go back to the past, how we can’t make that place exist again in the future, I am afraid that my work will be interpreted as me believing that there is a way back. No matter how my life and my feelings change and move on, the way I felt in those moments is calcified in that work. I don’t know if I can bear the responsibility of condemning someone to never get away from the sound of the woman who loves them, but maybe I have. I don’t want the sound of my voice to haunt them. All at once it’s narcissistic to think that it could and it’s naive to think that it won’t.

I don’t know if anyone’s ever used you as a muse or made a work of art about you - that’s something you can ask people when you want to be a bitch in a very specific way - but when it has happened to me I have poured over that work to try understand how that other person saw me. Not to be extremely Hegelian and annoying about it, but seeing someone seeing you is fascinating, torturous and almost entirely irresistible, at least to me.

I can’t help but situate myself on the other side of the keyhole to peer through at someone else’s view of me like a conceited Margaret Atwood fantasy. Even when someone says that a work of art reminds them of me, I file that information away in my brain to investigate further later. Whether it’s a song or a film or a painting, a sunset or a landscape, even a playlist or a picture they saw on Twitter of two unlikely animal friends, I remember.

The hard part is reminding myself that those people are not calling out to me across time whenever I revisit those things, even though the voice of the version of them that loves me still echoes. Once you make something about another person, what they do with it is out of your control. We should all be glad that we don’t have to perform it over and over for the world to see. If putting someone into your art is like pinning a butterfly in a glass case, performing it live like Silver Springs was is like hammering nails into a coffin while the body inside is still alive.

I think what really gives Silver Springs its magic is that we all have a place we wish we could go back to. The song doesn't just allow one person’s past self to reach out across time to someone in the present, it allows us to reach backwards as we listen to it, and spend a few minutes with one foot in the place where we used to be, while the other remains in the future.

Silver Springs sounds like missing the good times with the person I used to be with, and the person I used to be. It sounds like sitting on the floor with my best friend, playing Fleetwood Mac records on the same record player my dad had when he was a kid. It sounds like the drive out to take my grandmother to see the house she grew up in, only to find that it was completely different to how she remembered it. Maybe it’s important to preserve our past in art like this, even though the things the art is saying are no longer true. Much like the lonely, determined cry of Voyager 1’s record, all the art we make insists, “this was real, it happened, we were there.”

I don’t think that there’s anything I’ve said here that Stevie Nicks doesn’t already know. Maybe there’s just too much unfinished business between her and Lindsey Buckingham, maybe the story isn’t over yet, or maybe they just can’t leave each other alone. That’s for them to decide. The pair may never perform together again following the death of Christine McVie.

As for the rest of the world, the public have spent almost half a century and counting with the art that, for better and certainly for worse, could not exist without all the persevering contradictions of their shared history. As she usually does, Stevie Nicks said it best when she said of Lindsey Buckingham: “There’s nothing going on between you and me, except that there will always be something going on between you and me.”4

If you’re rocking with this, allow me to suggest adding this performance of Landslide that makes me want to throw up :)

One of the most widely circulated recordings of the song being performed is from The Dance (1997). I would also recommend checking out this one (also from 1997) where Stevie and Lindsey clearly have some crazy shit going on at the end. For the real freaks here is a moments compilation someone uploaded to YouTube 14 years ago - and boy, can you tell.

Fleetwood Mac on NBC Today Show with Rona Elliot, 1987. God bless everyone who digitised VHS recordings and put them on the internet.